Aid, whether it’s humanitarian or development, can feed into existing tensions or conflicts or worse, create new tensions. Why? We often infuse resources in environments where intergroup pressures, inequality, and scarcity of resources exists. So by bringing aid but without understanding the context and the dynamics, aid can increase tension unintentionally.

At the CSF, we work with Sudan’s aid system to help it become more conflict sensitive, or in other words, more aware of its context and the impact it has on that context, and better able to adapt to have as positive an impact on conflict dynamics as possible.

In our trainings and interactions with aid workers across the spectrum, we hear lots of ideas about what conflict sensitivity is – or isn’t. Some of these are right and others… need a bit of correction.

In this blog, we’re debunking some of the most common myths we hear about conflict sensitivity.

Myth #1: Conflict is always bad.

This is a prevalent myth! However, history tells us that most (maybe all?) of the world’s great social justice movements emerged through conflict. Peaceful, or non-violent responses to conflict have changed the lives of millions, perhaps billions, for better – Sudan has a few lessons to offer on this. Conflict is natural, and part of every interpersonal, intra-group, and inter-group relationship – it will always be with us. And that’s nothing to complain about. Our goal in conflict sensitivity is not to prevent conflicts, but to recognise them and seek to have a constructive effect – or at the least not a negative impact – on them through our work.

Myth #2: Conflict sensitivity is the same as risk management

Risk management seeks to identify, manage or mitigate risks to a project or programme. It includes risk to an organisation’s staff, operations, reputation, programs and finances.

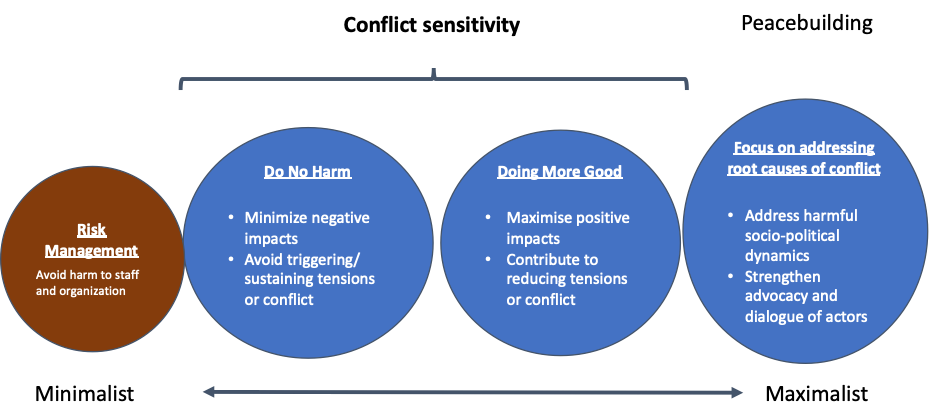

Conflict sensitivity, on the other hand, looks at how a project might affect the conflicts around us, and seeks to minimise and mitigate the risks that we might cause harm or contribute to these conflicts. If possible, conflict sensitivity says we should take it one step further, and aim to have our programs actually contribute to social strengths and peace.

This means we have to go beyond gauging whether our staff and projects might be threatened by a violent conflict and look at whether and how we are impacting the conflict dynamics in return. This action involves knowing one’s context (also see our Sudan context course rolling out later in June) and then being able to flexibly act on that analysis in order to minimise any potential harm done to the communities where we work.

Myth #3: Conflict sensitivity is just for peacebuilders

Conflict sensitivity is not just for peacebuilders! It applies to all peacebuilding, humanitarian, and development aid workers and aid organisations. If you’re a conflict sensitive aid practitioner, you understand the context you operate in and monitor it regularly through different forms of conflict analysis like those we mention above.

There’s a spectrum of ways to approach conflict. On the one hand, there’s risk management, which seeks only to guide and protect an organisation and its staff from harm stemming from conflict. On the other, there is peacebuilding, which strives to work directly on the root causes of conflict by identifying and addressing harmful systemic and socio-political dynamics and strengthens advocacy dialogue of actors.

Conflict sensitivity sits somewhere between these. On the one hand, it looks beyond the risks and opportunities that may impact an intervention (see myth #2). However, its ambitions are less lofty than peacebuilding programmes, which are devoted to unravelling the sticky, root causes of conflict. Instead, conflict sensitivity involves understanding how humanitarian and development interventions can trigger or sustain new or existing conflicts and, if more ambitious, adapt programmes to feed into positive impacts like contributing to social cohesion.

Myth #4: Conflict sensitivity always requires neutrality

Neutrality is one of the important, though arguably impossible, humanitarian principles. Taking – or being seen to take – sides in an ongoing political conflict is often a surefire way to aggravate disagreements and erode trust in your organisation or project. Yet sometimes our principles come into conflict with each other, and we find ourselves in situations where we can’t be both neutral and committed to responding to need wherever we see it. There are also some values and ideas which aid organisations are rightly committed to, whether that be gender equality or ending poverty that can challenge the wealth or power of others in society and attract criticism.

Navigating these kinds of dilemmas requires balancing commitments and interests, and managing risks. It is important to recognise that many predicaments pit short-term demands or risks against longer-term goals that could contribute to lasting and positive change. By embracing conflict sensitivity, these decisions won’t become easier to make. You will however be better prepared and informed for when you do so.

Myth #5: Conflict sensitivity goes against gender sensitivity

Promoting gender equality can provoke harmful reactions in some places, particularly in more conservative, patriarchal societies. Such backlash can be harmful to the project, to the individuals involved and to communities, particularly women and girls, in the surrounding area. At the same time, by skirting around deep inequalities and grievances like these that contribute to conflict, interventions can end up obscuring or even perpetuating them. Such trade-offs are very difficult to navigate but only by being aware of them and understanding them can we respond in the most meaningful way.

Gender norms and inequalities play a critical role in conflicts in Sudan and elsewhere. In many places for example, young men are seen as being the defenders of the community and pressure is put on them by women and the chiefs to fight. As a result, they often feel that they have no place in peacemaking. At the same time, women and girls play various roles in conflict, at times acting as peacemakers and other times as spoilers or inciters.

Looking ahead

Conflict sensitivity is not easy or straightforward. Operationalising a conflict sensitive approach requires changes in personal behaviour and institutional ways of working. Implementing a conflict-sensitive approach is not solely the responsibility of programme staff, but requires management buy-in and active support if it is to achieve genuine change.

The good news is that aid also has the potential to strengthen social cohesion, transform social conflict and amplify the intended benefits of our interventions IF we apply our conflict sensitivity lens to all areas of our operation, and if we change our attitude and behaviours around conflict sensitive aid implementation.

A lot of the information in this blog was taken from the CSRF Conflict Sensitivity Toolkit and Saferworld’s introduction to conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and peacebuilding.