By Audrey Bottjen

“One of the most bitter tragedies of Sudan is that the dilemmas facing humanitarian organisations today are almost exactly those faced repeatedly over the last ten years… But while the generals and guerrillas have learned their lessons, the UN humanitarian agencies have not.”

Francois Jean (MSF Evaluation 1993)

This analysis is the third blog of our blog series humanitarian access, local action and conflict sensitivity dilemmas in Sudan since April 2023 and Part I of a two-part series exploring lessons from Sudan’s history regarding the implications of humanitarian access on conflict dynamics. Part II explores the implications and recommendations of this analysis for policy and programmes and will be published soon.

Humanitarian access challenges in Sudan are not new. The control or denial of access by conflict actors to further political, military and economic agendas has persisted for at least 40 years, with serious implications for the human toll, as well as the nature of Sudan’s conflicts. This blog identifies lessons from the history of access in Sudan to help aid actors today navigate the access landscape in a conflict sensitive way. Many of these are not unique to Sudan (lessons from other fraught contexts, such as Syria, Yemen, Myanmar and Ethiopia are explored here), but the way that they manifest are influenced by Sudan’s particular history, geography, and resources.

Controlling access of humanitarian aid, as well as movements of people and resources more broadly, has been an important military objective in most, if not all of Sudan’s past wars. It has been used in counter-insurgency strategies aimed at depopulating hostile areas, as a tool to direct resources that can then be taxed or looted, or as a pull factor bringing internally displaced people (IDPs) into areas where they can be more easily controlled.

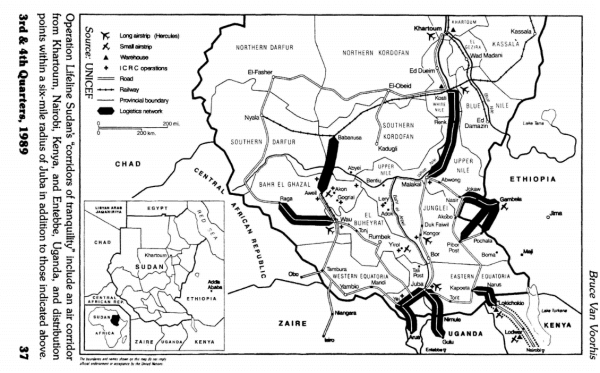

The Bahr el Ghazal famine of 1988-1989 that led to the beginning of Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) was not an accidental by-product of the 1983-2005 war, but part of a strategy of depopulating areas supportive of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), thereby depriving the insurgency of key sources of sustenance and recruitment.[1] At its inception, OLS sought to improve access by establishing ‘corridors of tranquillity’ through which humanitarians could safely provide aid. Despite challenges,[2] the initiative led to an innovative tripartite access agreement between the United Nations (UN), a sovereign government and a rebel group. Under this agreement, humanitarian access to the northern sector was negotiated with and delivered through Khartoum, and access to what is now South Sudan was negotiated with the SPLA and delivered through Kenya.[3] However, negotiations to provide assistance to the Two Areas of the Nuba Mountains and southern Blue Nile failed, and they were left out of OLS.

As in the earlier famine in Bahr el Ghazal, the access restrictions to the Nuba Mountains were coupled with both military and ethnically-based militia violence and intended to work as a counter-insurgency strategy, essentially starving a population into submission and preventing them from feeding or sheltering rebel movements. As part of the military strategy, the government asked UN agencies to provide aid within government-controlled ‘peace camps’. These camps were set up by the state to receive, control, and exploit displaced populations in efforts to prevent them from supporting or joining the opposition. “With promises of food, government or rebel factions can coax civilians to areas under their control and hold them, thereby adding weight to constant arguments for more.”[4] This resulted in criticisms that by providing aid in government-held areas only, and by extension allowing one side of the conflict to extract military benefit, the aid sector’s claim to neutrality was discredited.[5]

Humanitarian access into Darfur in the early 2000s highlights a different, but equally relevant set of military implications for access. Because NGO or UN agencies working from Khartoum were required to receive military intelligence or HAC permissions for their local hires, it was assumed that some humanitarian staff were covert government agents. Rebel groups therefore perceived that the aid effort was not independent or neutral, and denied access to many NNGOs, and required names of all aid actors before granting access permission.[6]

Humanitarian access also has political implications in Sudan, and conversely, politics have affected humanitarian access. Decisions about when, where and with whom to negotiate access can give those actors power over where aid goes and build their legitimacy and credibility. This relates not only to engagement with state and non-state actors, but also – especially in a context of chaotic state entropy – who within institutions is empowered. The actors within the Sudanese government have always had a range of interests and ambitions, particularly between national, state and locality levels, and this has only accelerated in recent months. Managing this political complexity requires strong principles.

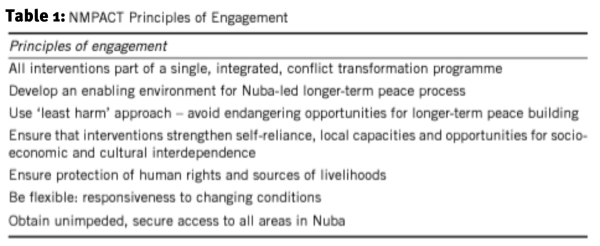

The Nuba Mountains Programme Advancing Conflict Transformation (NMPACT) from 2002-2007 highlights how principles can be used effectively to contribute to meaningful access and reduce the impact of conflicts on affected populations.[7] NMPACT’s approach to principles, outlined in table 1, contrasts markedly with OLS, which was not intended to have any interaction with peace or conflict drivers.[8] NMPACT was supported by having a mandate for addressing the root causes of conflict, deep stakeholder and community-level engagement and also high-level diplomatic support. Notably, from an access perspective, “The humanitarian embargo on the Nuba Mountains was ended not through negotiations over humanitarian access, but diplomatic pressure….”[9] Believing that the war was unwinnable and that it was possible to take steps towards peace negotiations, diplomats negotiated a series of confidence building measures, which included aspects of access. Critical to the success of this programmatic and diplomatic approach to access was a flexible monitoring and reporting system, the Joint Monitoring Mission/Joint Military Commission, comprising Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), SPLA and international members with the authority to approve their own flights and the mandate of investigating and responding to ceasefire violations.

The Nuba Mountains Programme Advancing Conflict Transformation (NMPACT) from 2002-2007 highlights how principles can be used effectively to contribute to meaningful access and reduce the impact of conflicts on affected populations.[7] NMPACT’s approach to principles, outlined in table 1, contrasts markedly with OLS, which was not intended to have any interaction with peace or conflict drivers.[8] NMPACT was supported by having a mandate for addressing the root causes of conflict, deep stakeholder and community-level engagement and also high-level diplomatic support. Notably, from an access perspective, “The humanitarian embargo on the Nuba Mountains was ended not through negotiations over humanitarian access, but diplomatic pressure….”[9] Believing that the war was unwinnable and that it was possible to take steps towards peace negotiations, diplomats negotiated a series of confidence building measures, which included aspects of access. Critical to the success of this programmatic and diplomatic approach to access was a flexible monitoring and reporting system, the Joint Monitoring Mission/Joint Military Commission, comprising Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), SPLA and international members with the authority to approve their own flights and the mandate of investigating and responding to ceasefire violations.

Economic factors can drive and sustain conflicts, and humanitarian access interacts with both short-term and longer-term economic trends. On one hand, access into areas can shape patterns of resource flows. This relates most obviously to the aid resources themselves, but the economic ripple effects from aid operations go much further, including impacts on checkpoint economies, armed actors taxing or looting aid, and other rent-seeking behaviour.[10] On the other hand, the strategic denial of access can have pernicious implications. The patterns of access denial from 1983-1986 led to a substantial shift in wealth away from rural areas and into the military-dominated economy of Khartoum’s political elites.[11] Joshua Craze describes this happening in several ways:

The economic dimensions of access denial have been a feature of many of the conflicts since that time, by different actors including the SPLA, and continue to put into motion trends that drive conflicts and vulnerability. Understanding the economic and livelihood implications of humanitarian access will help contemporary aid actors to design strategies and initiatives mitigating some of these challenges.

[1] While this study is focused on South Sudan, it is very relevant to analysis of checkpoints in Sudan as well. https://www.csrf-southsudan.org/repository/checkpoint-economy-the-political-economy-of-checkpoints-in-south-sudan-ten-years-after-independence/

[2] Craze, Joshua. Displacement, Access and Conflict in South Sudan: A Longitudinal Perspective. Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility. 2018.

[3] Costa, Mauro. Two Areas Context Course for Aid workers. Conflict Sensitivity Facility. 2023.

[4] Pantuliano, Sara. Responding to Protracted Crises: The Principled Model of NMPACT in Sudan.

[5] Bradbury and Eldin, Evaluation of the Nuba Mountains Programme Advancing Conflict Transformation (NMPACT), 24

[6] Loeb, Jonathan. Talking to the Other Side: Humanitarian Engagement with Armed Non-State Actors in Darfur, 2003-2012. HPG Working Paper. ODI. 2013

[7] Peterson, Scott. Me Against My Brother: At War in Somalia, Sudan and Rwanda. Routledge. 2014.

[8] Bradbury, Mark. Sudan: International Responses to War in the Nuba Mountains. Review of African Political Economy. 1998.

[9] There are far more legacies of this agreement and the modalities of how OLS was implemented than can be covered in this short analysis. For more analysis, suggested readings include: Leben Moro’s piece, Bradbury maybe?

[10] Human Rights Watch. Crises in Sudan and Northern Uganda. 1998. Access article here.

[11] Including substantial numbers of flight bans restricting humanitarian access to many areas and a number of government attacks on relief centers.