The Conflict Sensitivity Facility (CSF) has identified four key ‘windows of opportunity’, covering issues where the aid sector has the potential to either contribute to ongoing or future conflict over the long term, or to contribute to peace. We’ll discuss these windows in a series of blogs aiming to encourage discussion, debate and good ideas for how the aid sector in Sudan can improve its long-term impact. This blog will focus on aid and land.

Land use and land rights are at the heart of some of Sudan’s longest-running conflicts. Displacement, the uprooting of people from their land, is a major part of that story. Displacement also drives humanitarian need and hinders development and peacebuilding efforts. Many types of assistance, including WASH, livelihoods, humanitarian aid to IDPs and refugees and governance interact with these dynamics but are not always guided by an understanding of the social, economic and political implications of their work.

Currently, around 3.6 million people in Sudan are displaced but many millions more have faced economic, climate and conflict-driven displacement over the last century, especially in Darfur, Southern Kordofan, Blue Nile and the Eastern states.[1] Policies investing in large-scale, irrigated farming were first enacted in the colonial period to produce cotton for British textile mills. In the 1970s, they were bringing more land under large-scale cultivation and forcing many Sudanese smallholders off their land in the process. In the last 20 years, the government millions more acres to foreign corporations, particularly from the water-scarce Gulf States. Large infrastructure projects such as dams have also resulted in a large movement of people, most notably the Aswan and Meroe dams, the results of which are still being felt today.

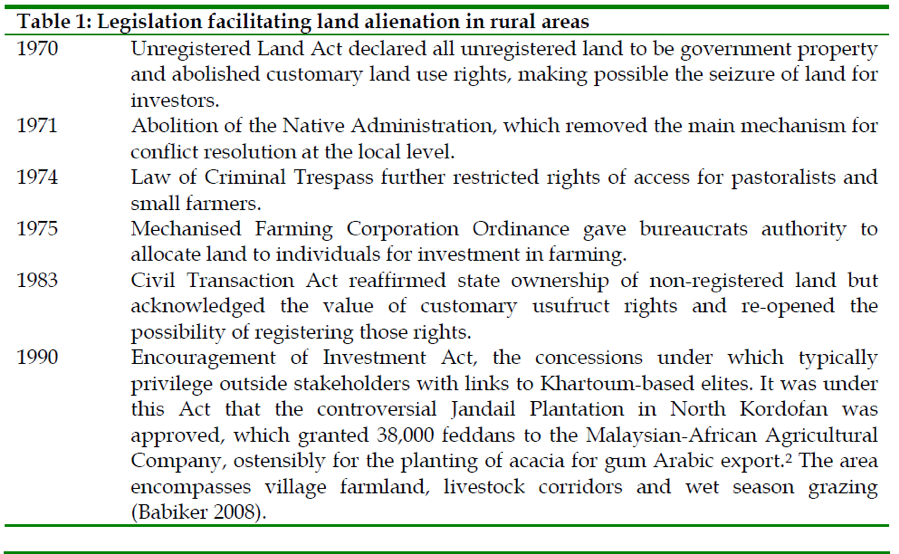

This land expropriation is enabled by legislation that promotes the interests of the over customary land use and land tenure systems. The winners of this system tend to be from a small group of economic and political elites.[2] The losers are the regular waves of small-scale farmers forced off of their land and into urban poverty, exploitative wage labour on industrial farms, or artisanal mining.[3] These practices, along with similar practices dispossessing people from their land for the construction of dams and the drilling of oil, have contributed to marginalisation and the unaccountable use of natural resources that is and will be a major factor of unrest in Sudan going forward.

Figure 1: El Hassan and Birch. Securing Pastoralism in East and West Africa: Protecting and Promoting Livestock Mobility. 2008.

Other forms of displacement have an even more direct linkage to conflict. The long-running wars between Khartoum and Sudan’s peripheries are often focused on the control of people and their land. Scorched earth tactics, whether by the Sudan Armed Forces or the related paramilitary forces, were designed to separate resisting populations from their sources of livelihoods, protection and strength, rendering them dependent on outside assistance, which was often controlled to some degree by the Khartoum regime.

Scorched earth tactics, whether by the Sudan Armed Forces or the related paramilitary forces, were designed to separate resisting populations from their sources of livelihoods, protection and strength, rendering them dependent on outside assistance, which was often controlled to some degree by the Khartoum regime.

Displacement has become a vital component in Sudan’s fragile transition and one where donors, policy-makers and aid actors will exercise considerable influence. First, the transition will have to design durable solutions for the millions of internally displaced persons and refugees. Though the response to displacement and returns is likely to fall to the humanitarian community, how and where these returns happen has direct implications for livelihoods and the economy. Land policy and land reform will shape the context for all of these activities, from the humanitarian toolkit around ‘Housing, Land and Property’ (HLP), to more complex policy discussions around the appropriate nature of agricultural policy in a context of climate change.

Aid actors working on or impacting these dynamics are generally not well enough informed of the context or of the programming approaches and policy options available to them. At the same time, humanitarian actors too often don’t understand many traditional land use and ownership policies, or how (re)settlement patterns might interact with livelihood options down the line. Development and agricultural policy makers are reportedly holding onto older models of large-scale mechanised farming that centralise land ownership and agricultural production into the hands of a few, wealthy (and sometimes) business families, dispossessing and keeping poorer families in poverty.[4] This has especially profound impacts on women from the most disadvantaged backgrounds, who often have less-secure land rights, less access to agricultural inputs, credit, extension services, community decision-making, or access to justice to protect themselves.[5]

Land policy and land reform will shape the context for all of these activities, from the humanitarian toolkit around ‘Housing, Land and Property’ (HLP), to more complex policy discussions around the appropriate nature of agricultural policy in a context of climate change.

Complicating matters, some of the productive land abandoned during the past years of conflict is now being used by new groups, including displaced communities, economic opportunists, or ‘armed settlers’ – particularly in Darfur. Seasonal, annual and less regular movements have long been part of a livelihood strategy of many Sudanese communities over the centuries, making it difficult to name specific geographic areas as ‘belonging’ to one group to another in a true historical sense. Yet, a narrative of conflict-related displacement, loss and grievance, remains powerful and in recent memory for many. Groups that have been armed and empowered by conflict actors continue to hold onto valuable lands. This is also true of groups associated with state military actors, particularly in mining areas.[6] Traditional leaders, who might be expected to play a role in community conflict resolution exercises have long been politicised by the previous regime, sometimes undermining their credibility particularly in the eyes of displaced communities and youth.

There will be no easy answers for aid workers seeking to be conflict sensitive as they work on and around land issues, but it is clear that this is an area where communities, government, donors, diplomats, UN and NGOs must collaborate and apply the best analysis possible into creative approaches.

The CSF intends to support these efforts through an upcoming roundtable, more analysis and problem-solving with interested organisations. We invite you to be in touch if you’d like to be part of these conversations – reach us at info@csf-sudan.org.

[1] James, Laura. Fields of Control: Oil and (In)security in Sudan and South Sudan. Small Arms Survey. 2015.

[2] Among their customers were aid organizations procuring food locally for humanitarian relief efforts. See Susanne Jaspar’s The State, Inequality, and the Political Economy of Long-term Food Aid in Sudan. African Affairs. 2018.

[3] Schwarstein, Peter. One of Africa’s most fertile lands is struggling to feed its own people. Bloomberg News. April 2019. Accessed online 27 Dec. 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2019-sudan-nile-land-farming/

[4] Thomas, Edward and Magdi El-Gizouli. Sudan’s Grain Divide: A Revolution of Bread and Sorghum. Rift Valley Institute. February 2020.

[5] Hamduk, Adam Ahmed. El Fasher Field Report. Dec. 2020.

[6] Rift Valley Institute. Security Elites and Gold Mining in Sudan’s Economic Transition. Rift Valley Field Update #2. May 2019

Photo credit: Eric Kevorkian (Heiban County, South Kordofan, 2017).